Where is the pause?

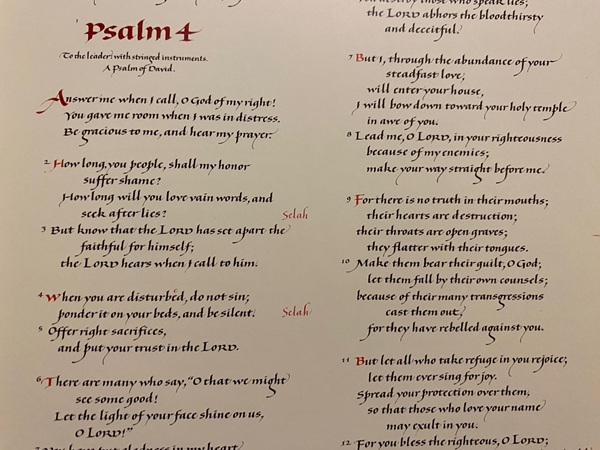

In all likelihood, you have never consciously heard the word »Selah«, even though you have likely encountered it while reading the bible. This word appears 74 times in the Old Testament – 71 times in the Psalms and 3 times in the book of the prophet Habakkuk. Scholars are unsure of the word’s origin.

However, drawing on the frequency of selah’s position at the end of a poetic verse or phrase, many scholars have concluded that selah was a musical term that meant to »pause« or »contemplate« - like the current rest notation used in a musical score. Instrumentalists, for instance, might have continued playing while the chorus or congregation stopped briefly.

The idea in the Hebrew for this word is a pause. Some think that this was a musical instruction, perhaps calling for a musical interlude of some kind. But most scholars think Selah speaks of a reflective pause, a pause to meditate on the words just spoken. Maybe it was both - »meditate on these words while you listen to this music«.

We need »selah«. We need to practice »selah« in our lives as well as in music. Or to put it another way: Where is the pause?

We race through texts and music, but also through our experiences. Hardly has something been said, played or performed, and already we are adding our 5 cents worth. Commentary is our fallback position on everything. It presupposes that we have understood what has just happened, that we need neither time nor effort to delve deeper into what has just transpired.

Permit me a story. 26 years ago, I was privileged to hear Itzhak Perlman perform the iconic violin solo from Schindler's List (1993). The moment his playing ended the audience was on its feet and thunderous applause resounded through the theater. I sat quietly and was horrified by this. When I did not rise or applaud, a few moments later I was roughly shoved on the shoulder and told by an irate American: »Get up, you Philistine. Don’t you appreciate greatness when you hear it?« It is a memory as fresh in me today as on the day it occurred.

On that evening, I did not rise and applaud because of a lack of admiration or respect for the performance or the composition. It was greatness indeed. But I posed the question back then and with considerably more urgency today, as to whether applause is the only response, let alone the appropriate response, to this music. This piece of music has often been described as a »conversation between pain and beauty«. Why are silence, reflection, emotional speechlessness, tears or simply being overwhelmed by it all not even considered as an option? Where is the selah? Where is the pause?

Days before the concert I had read the back story of this composition, helping me understand what went into the creation of this melody. The composer, John Williams recounts: »Spielberg showed me the film ... I couldn't speak to him. I was so devastated. Do you remember, the end of the film was the burial scene in Israel - Schindler - it's hard to speak about. I said to Steven, 'You need a better composer than I am for this film.' He said to me, 'I know. But they're all dead!’« Pausing to learn the story behind the story is »selah«.

I still vividly remember watching Itzhak Perlman’s face* while he was playing the piece, and it was an unveiling unto itself. I watched a human face move and change and flow with the melody, the flashes of concentration and emotion that themselves were telling me a story. I saw the face of a man who was utterly affected by what he was playing. Watching, admiring and being touched by what is transpiring are also »selah«.

More than anything else, I recall the feeling of the moment. I paused to savour all the ways this music stirred my soul, moved my heart, released my tears and weighed on my thoughts of the Shoah. I let the images it awakened meander through my mind. This too is a »selah«, the ability to savour and relish all the flavours and colours and textures of an experience, that are swiftly lost when we rush past them.

There are things to which we cannot do justice without the »selah«, the pause to reflect and allow ourselves to take a long loving look at the real. My pause in that theater so many years ago was my applause.

Recently I spoke of this with my beloved teacher. He asked me what had brought back the memory, and I told him of a homily I had just preached. I had spent 40 hours writing and refining it. I had put many more hours into researching and reflecting on the text. And many years of teaching, researching, study and reflection, of wrestling with the linguistic nuances of Greek, Hebrew, French, English and German, flowed into that homily. Twenty minutes after Mass, when I left the church, I was approached by people who had formed a little group. They had discussed my homily and informed me of the consequences they had drawn, including an inconsistency between the homily I had preached and a moment in the liturgy. I was not insulted, but I was taken aback. Where is the »selah«? Where is the pause that allows for reflection? This was the reason I was suddenly transported back to that concert hall 26 years ago.

In his inimitable wisdom, my beloved teacher said to me: Tell the story. It was only while I was sitting down to write these words, that I realised I had never once told the story since the day I experienced it. My »selah« took 26 years. And yet, even now, I would never dare to suggest, that I have fully understood the breadth and depth of that moment. I am still sitting in that theater and pondering. I think Itzhak Perlman and John Williams would approve.

*If you would like an inkling of the experience you can see for yourself:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cLgJQ8Zj3AA

Erik Riechers SAC

Vallendar, February 5th, 2026